Put Down the Whip

Why we can’t turn one moment into permission for cruelty

There’s a peculiar kind of Christian who lights up when they talk about Jesus flipping tables in the Temple. Their eyes get a little brighter. Their posture straightens. Finally, they seem to say, here’s the Jesus who vindicates my anger, my sharp tongue, my public callouts, my refusal to budge. Here’s the Jesus who says it’s okay to be mean if you’re right.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately because I keep seeing it, particularly in my comment sections. In the way some people talk about their political opponents or their theological enemies. They’re not interested in “love your enemies” or “blessed are the peacemakers” or “turn the other cheek.” Those teachings get a polite nod, maybe a quick “yes, but—” before we rush headlong into the one story that lets us off the hook. The one where Jesus gets mad. The one with the whip.

Last week, I received a dozen comments like this one:

The Table I Grew Up At

I grew up in a church where righteous anger was practically a spiritual gift. If you could Bible-verse someone into a corner, if you could out-quote them, out-debate them, out-conviction them, you were seen as spiritually mature. Strong. Uncompromising. We weren’t mean, we told ourselves. We were just speaking truth. And if people got hurt, well, Jesus flipped tables too, didn’t he? Well, we need to talk about that.

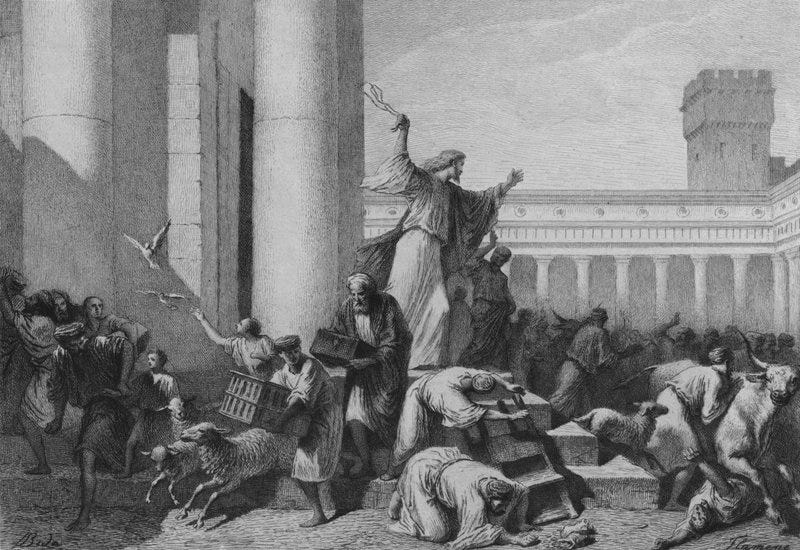

What Actually Happened at the Temple

Here’s the thing: we’ve turned the Temple incident into something it wasn’t. We’ve made it a blank check for our own rage, a permission slip to be unkind in the name of truth. But if we slow down and actually look at what happened, the story gets a lot more complicated.

Amy-Jill Levine, a Jewish New Testament scholar, has spent years pushing back on the way Christians have misread this moment1. She points out that the Temple was massive, sprawling across an area that would cover dozens of modern soccer fields. Flipping a few tables wouldn’t have shut anything down. It was symbolic, not practical. It was prophetic theater, a dramatic gesture meant to draw attention to something deeper.

And what was that something? This may surprise you, but it wasn’t the money changers themselves. It wasn’t at the price gouging or exclusionary policy (which is what I had always been taught.) Levine argues that there’s no textual evidence the vendors were exploiting anyone. Instead, she notes that money changing was a necessary service. Pilgrims came from all over the world with foreign coins that couldn’t be used in the Temple. Someone had to exchange them. Therefore, this wasn’t corruption, it was simply logistics.

So what was Jesus actually angry about, then? Levine suggests it was about the disconnect between worship and ethics. It was about people who showed up at the Temple, performed their rituals, said their prayers, and then went out and lived lives marked by injustice. They used the Temple as a refuge, or a spiritual safe house, while continuing to exploit the vulnerable and ignore the commands of God. That’s what “den of robbers” means. Not a place where robbery happens, but a hideout where robbers go after the fact, thinking they’re safe because they’ve done their religious duty.

Jesus wasn’t condemning the Temple system itself. He and his followers kept going there. This was an internal critique, a call for reform, a prophetic demand that worship and life align. It was Jeremiah all over again: “Will you steal, murder, commit adultery, swear falsely, make offerings to Baal, and go after other gods that you have not known, and then come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my name, and say, ‘We are safe!’, only to go on doing all these abominations?”

The Gospel We’d Rather Ignore

Here’s what gets me: we’ve taken this one moment, this one story of disruption, and turned it into the defining image of Jesus. Meanwhile, we’ve somehow managed to downplay or ignore the overwhelming majority of his life and teaching. The Sermon on the Mount. The parables of mercy. The woman caught in adultery. The lepers he touched. The tax collectors he ate with. The enemies he told us to love. The forgiveness he offered from the cross.

Jesus spent his entire ministry embodying compassion. He wept over Jerusalem. He healed on the Sabbath and took the heat for it. He let a woman wash his feet with her tears. He stopped a stoning. He rebuked his disciples when they wanted to call down fire on a Samaritan village. He told Peter to put away his sword. He prayed for the people executing him.

And yet somehow, we’ve decided that the one time he got angry in the Temple is the real Jesus. The unfiltered Jesus. The Jesus who justifies our harshness, our cruelty, our refusal to extend grace. We cling to that whip like it’s the only tool in the Kingdom of God.

It’s not just bad theology. It’s lazy. It’s self-serving. And honestly, it’s gross.

What We’re Really After

I think the reason we love the table-flipping story so much is because it lets us off the hook. Love your enemies is hard. Turning the other cheek is costly. Forgiving seven times seventy feels impossible. But righteous anger? That comes easy. That feels good. That lets us be mean and still feel holy.

We want a Jesus who endorses our culture war tactics. We want a Jesus who backs our Facebook dunks and our hot takes and our refusal to listen. A Jesus who says it’s okay to burn bridges as long as we’re right. A Jesus who looks a lot like us when we’re at our worst.

But that’s not the Jesus of the Gospels. That’s not the Jesus who said the world would know his followers by their love. That’s not the Jesus who told us to bless those who curse us, to pray for those who persecute us, to go the second mile. That’s not the Jesus who, when given every reason to lash out, chose mercy instead.

If we’re going to follow Jesus, we have to follow all of him. Not just the moment that makes us feel justified. Not just the story that gives us permission to be harsh. We have to sit with the discomfort of enemy love. We have to wrestle with the scandal of grace. We have to let the Sermon on the Mount shape us more than our anger does. (I am currently writing about my personal struggle with this.)

Living Beyond the Whip

So what does this mean for us?

It means we stop using the Temple incident as a weapon. We stop reaching for it every time we want to justify our unkindness. We stop pretending that one moment of prophetic disruption erases three years of radical compassion.

It means we ask ourselves harder questions. Am I defending truth, or am I defending my right to be cruel? Am I calling out hypocrisy, or am I just venting my rage? Am I actually concerned about justice, or do I just like the feeling of being right?

It means we take seriously the fact that the same Jesus who flipped tables also washed feet. The same Jesus who called out religious leaders also ate with sinners. The same Jesus who disrupted the Temple also welcomed children. And when we have to choose which image to follow, which posture to embody, we choose the one that defined his entire life, not just one afternoon in Jerusalem.

Because here’s the truth:

The world doesn’t need more Christians who are good at being mean. It needs Christians who are good at being kind.

It needs people who can hold truth and grace in tension, who can speak prophetically without dehumanizing, who can challenge systems of injustice without using those challenges as an excuse to be cruel.

The table-flipping story isn’t a permission slip, it’s a warning. It’s a reminder that when worship becomes disconnected from the way we live, when our rituals don’t lead to justice and mercy, we’ve missed the point entirely. And if we’re using that story to justify our unkindness? Then we’re the ones who’ve turned the Temple into a den of robbers. We’re the ones hiding behind our religion while living lives that contradict everything Jesus taught.

Maybe it’s time we put down the whip and pick up the towel instead.

If this piece gave you something new to think about, or just helped you see Jesus a little differently, would you consider supporting my work? You can become a paid subscriber or simply buy me a coffee below. Either way, it helps me keep writing words that (I hope) build bridges, not walls.

Levine, Amy-Jill. Entering the Passion of Jesus: A Beginner’s Guide to Holy Week. Abingdon Press, 2018, pp. 45–62. Chapter 2, “The Temple: Risking Righteous Anger.”

I like this a lot. You can only grab the whip verse if you’ve already touched a leper and had dinner with a tax collector. Reminds me of Rich Mullins saying how much he liked highlighters so he could just highlight the Bible verses he liked :D Thanks.

The 'righteous anger' argument is deeply embedded here in [mostly white] hyper conservative evangelical Bible Belt America. I have witnessed angry dad/husband preachers first hand who should be immediately removed from pulpits and any place of authoritarian influence until they have dealt deeply with the emotional rage held so tightly in their wounded souls. Sadly, this Boomer-WarBaby era of believers and congregations seem to exalt, platform, and monetize such behavior, all in the name of 'holiness' and 'righteousness'.

God help our American churches. And, God forgive us as we confess, repent, and turn away from our wrath-filled experiences and into a spiritual baptism of Goodness and Kindness. This is truly The Better Way.