Why I Can Take the Bible Seriously Without Taking It Literally

Part 2: What Archaeology Reveals About How to Read the Bible

I’m teaching a three-week class on biblical reliability right now, and a question that keeps coming up is this: “If I don’t believe everything in the Bible happened exactly as written, does that mean I don’t take it seriously?”

It is such a great question, and the honest answer? I believe there is some great archaeological evidence that actually gives us permission to take the Bible more seriously than ever before. Because when you understand what kind of texts you’re reading and the historical world they emerged from, you can engage Scripture with both intellectual honesty and deep respect.

For week 2 of this series, here’s what I’ve been sharing with the class about how archaeology helps us distinguish between historical grounding and strict literalism.

Real People in Real Places (With Real Literary Freedom)

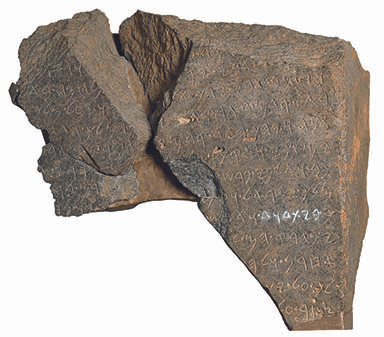

In 1993, archaeologists discovered a broken stone monument at Tel Dan in northern Israel with six words carved in ancient Aramaic: “House of David.” This was an enemy inscription from the ninth century BC celebrating victory over David’s royal line. Before this, scholars debated whether King David was even real. Welp, that debate ended in 1993. He was real.

Then, in 2015, archaeologists found a royal seal impression: “Belonging to Hezekiah, son of Ahaz, king of Judah.” The Bible devotes multiple chapters to Hezekiah in Second Kings and Second Chronicles. You can walk through Hezekiah’s Tunnel today that he built to bring water into Jerusalem. The seal is there. The tunnel is there. No doubt, Hezekiah was real.

I mean these findings are cool, but here’s what I think this teaches us. Archaeological confirmation that David and Hezekiah existed doesn’t mean every detail in their stories happened exactly as described. Ancient historians had different standards than modern historians. They shaped narratives to make theological points and they arranged events thematically rather than chronologically. They also included speeches that captured essence rather than word-for-word transcripts.

Taking these texts seriously means understanding them as ancient historical narratives, and that is okay. The writers weren’t inventing characters in imaginary kingdoms or anything, they were describing real people in real places while using the literary conventions of their time to communicate theological truth and we can trust the historical grounding without demanding that every conversation happened verbatim or every number is precisely accurate. I hope that makes sense.

The Gospels Work Like Eyewitness Testimony

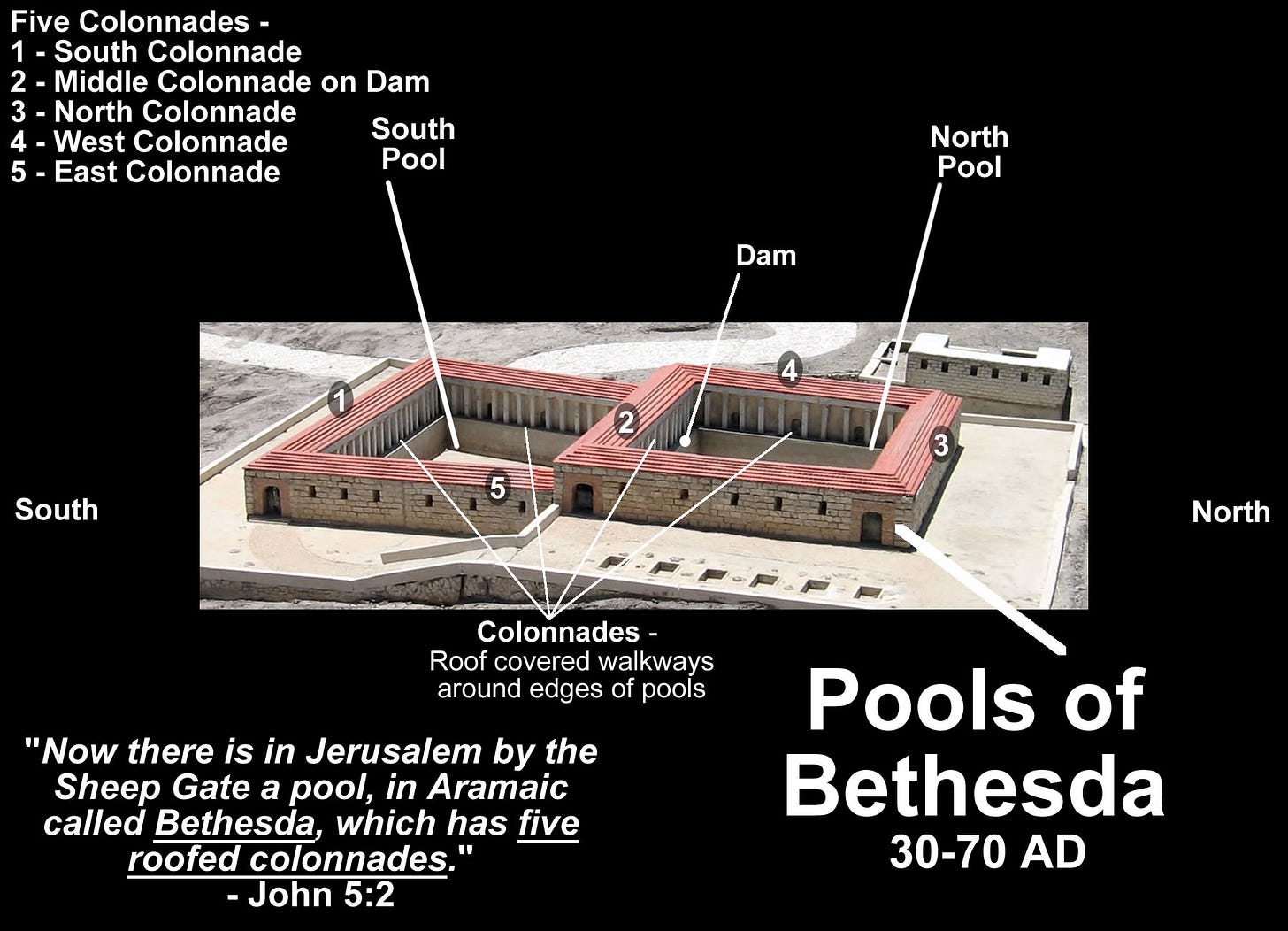

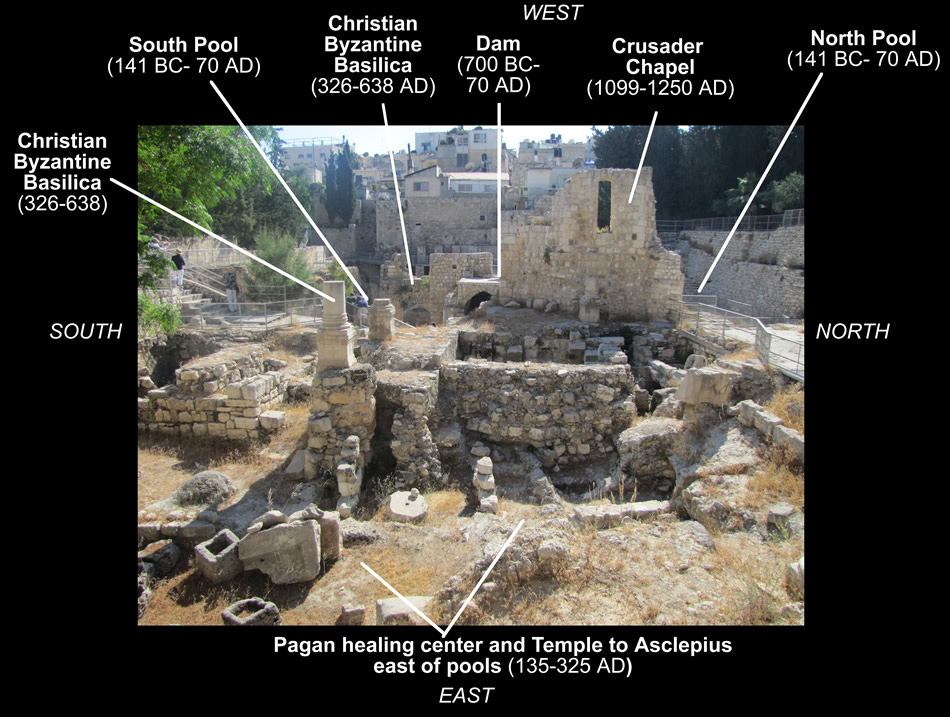

The same can be said about the New Testament. The archaeological evidence that has been found is remarkably specific. In John’s Gospel it describes the Pool of Bethesda near the Sheep Gate as having five covered colonnades. Well, in the late nineteenth century, excavations uncovered exactly what John described. They found a double pool with four colonnades around the edges and one in the middle. Five colonnades. John was describing an actual place he’d actually seen. How cool is that?

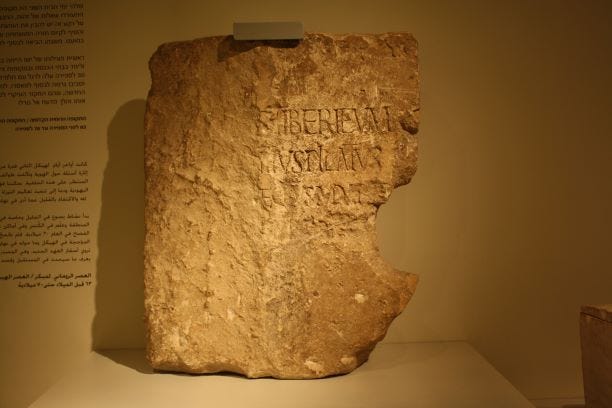

Then, in 1961, archaeologists found a limestone block with the inscription “Pontius Pilate, Prefect of Judea.” That same year, construction workers found an ossuary inscribed with “Joseph, son of Caiaphas,” almost certainly the burial box of the high priest who presided when Jesus was tried.

The Gospel writers got the details right because they were there or talked to people who were. They knew Jerusalem and they knew the geography. They knew who held what positions and when.

But here’s what taking the Gospels seriously actually means. These writers weren’t court reporters producing transcripts, they were simply interpreting the significance of what they witnessed. They arranged events to make prove points that were significant to them. They shaped Jesus’ teachings into memorable forms. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John sometimes tell the same story differently because they’re emphasizing different aspects.

Taking the Gospels seriously means recognizing them as interpreted testimony but told by writers who cared deeply about communicating who Jesus was and what his life meant. You don’t have to harmonize every detail to trust that you’re encountering reliable witness to actual history. Four witnesses to a car accident will tell the story differently depending on where they stood. That doesn’t make them unreliable, it simply makes them human.

Why Historical Grounding Actually Matters

In 1968, archaeologists found an ossuary containing bones of a man named Yehohanan. A seven-inch iron nail was still driven through his heel bone. This is the only archaeological evidence of Roman crucifixion ever found, and it confirms exactly what the Gospels describe. Nails through feet. Legs broken. Brutal but accurate to what we see in the biblical text.

This discovery matters because it reminds us that the Incarnation is a claim about what actually happened in history. God became flesh, lived a real life, died under actual Roman execution, and according to Christian witness, rose again.

The archaeological evidence is extensive. The Roman historian Tacitus, writing around 116 AD and despising Christians, still confirms that Christ was executed during Tiberius’s reign by Pontius Pilate. Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian born years after Jesus died, mentions Jesus twice in his work from 93 AD, confirming he lived, taught, attracted followers, was accused by Jewish leaders, and was crucified under Pilate.

No serious historian doubts Jesus existed. The evidence is too strong. But taking that historical grounding seriously doesn’t require believing every healing happened exactly as described in every Gospel. It means believing God entered human history in a real person at a real time in a real place. It means the resurrection claim is about something that happened to an actual body.

You can take the Incarnation seriously as a historical claim while still recognizing that the Gospel writers shaped their accounts theologically.

What This Means for How You Read Scripture Now

If there is anything I would like people to take away from this class/series, it’s that taking the Bible seriously actually requires not taking everything literally. Because forcing ancient texts into modern categories is actually doing it a disservice.

Archaeological evidence gives us permission to engage Scripture with both intellectual honesty and deep reverence. Sure, the people were real. The places were real. The historical grounding is there, but the texts use different genres, different literary conventions, and different ways of expressing truth.

When you read historical narratives, remember you’re reading ancient historical writing with its own conventions. When you read the Gospels, remember you’re reading interpreted testimony from people who were there. When you read poetry, let it be poetry. When you read prophecy, start with its original context. God gave us a brain, and we need to use it.

So yes, you can take Scripture seriously without taking everything literally. And archaeology, rather than undermining faith, actually strengthens it by showing us that our sacred texts are rooted in actual history, told by real people who knew what they were talking about.

Sometimes the most faithful reading is the one that lets Scripture be what it actually is rather than forcing it to be what fundamentalism demands it must be.

I write this newsletter independently. If you value this perspective, a paid subscription ($8/month) or a $5 cup of coffee helps keep it sustainable.

Thank you, Beau — as a scientist, I ran away from the Bible for decades. But the mystery brought me back. When I stopped fact-checking, the mystical nourishment of the Word opened up to me.

Now a daily reader of the Bible, curiosity and imagination help me approach God’s sacred story with a soft, attentive heart. I love it. 💜🙏🏽

A lot of people, especially in Gen Z, aren’t leaving Christianity because of science; they’re leaving because we taught them faith requires ignoring it. What you show so well here is that science actually turns out to be an ally.