Is Your Bible Reliable? The Answer Might Surprise You

Part 1: The Missing Originals

Before we dive in: I typically write these longer essays a few weeks ahead of publication, which means I can't always respond to breaking news in this format. For real-time thoughts on current events, you can find me on Threads.

I’m teaching a three-week class right now on a question that keeps coming up in my conversations with people who are deconstructing their faith.

Can we actually trust the Bible we hold in our hands today?

Over the next few weeks here on Becoming Mainline, I’m going to walk through the same material I’m covering in the class, but in a way that’s hopefully very accessible. This is part 1 of 3, and I need to tell you something right up front that might make you uncomfortable.

If you didn’t know, we don’t have the original manuscripts of the Bible. Not one. Not Genesis. Not the Gospel of John. Not Paul’s letter to the Romans. The actual pieces of papyrus that Moses touched, that Paul wrote on, that John penned are all gone.

I know what you’re thinking. You’re wondering if I’ve lost my mind bringing this up in the first week of a series on trusting the Bible. But stay with me, because what I’m about to tell you might actually be the most reassuring thing you’ll hear all week.

The Ancient World Didn’t Do Originals

Here’s something that helps put this in perspective. We don’t have Shakespeare’s original handwritten copy of Hamlet either. Or Plato’s original writings. Homer’s Iliad? Gone. In fact, we don’t have the original manuscripts of any ancient literature. Not one single piece. This is just how the ancient world worked, and it worked this way for a very practical reason.

Ancient people wrote on papyrus, which is basically pressed plant material, or on animal skins called parchment.

Think about how long paper lasts in your garage. Think about what happens to a book left in a damp basement. These organic materials decompose. They’re incredibly fragile. A few hundred years is pushing it for these materials. A thousand years is nearly impossible without absolutely perfect storage conditions that almost never existed in the ancient world.

So every ancient text we study today, whether it’s philosophy or history or religious writings, comes to us through copies. The originals crumbled to dust centuries ago. But here’s where the Bible’s story gets interesting.

The Manuscript Olympics

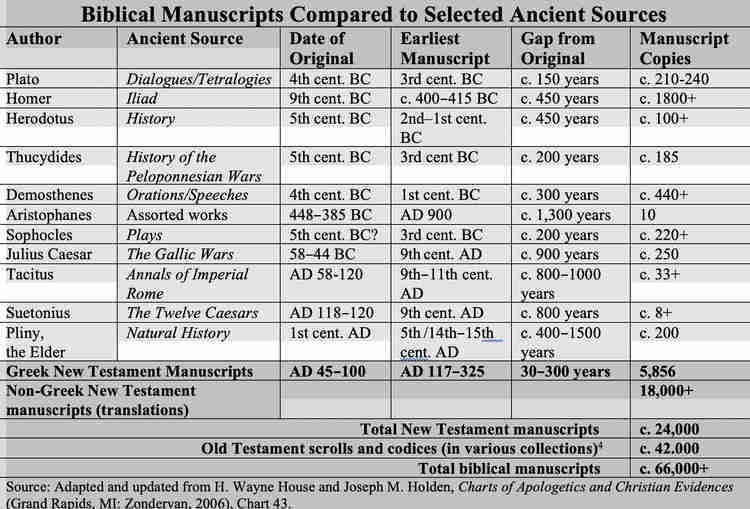

Even though we don’t have the originals, we have something that’s arguably even better. We have copies. Thousands and thousands and thousands of copies. Let me show you what I mean by comparing the Bible to other ancient texts that scholars trust and use every single day. Look at this chart:

The New Testament alone has roughly 24,000 manuscript copies. That includes nearly 6,000 copies in the original Greek, about 10,000 in Latin, and over 10,000 more in other ancient languages like Syriac and Coptic and Armenian. 24,000 manuscripts of the same text, all of them copied and preserved across centuries.

Now look at Homer’s Iliad, which is one of the most important pieces of ancient Greek literature. It’s taught in universities everywhere. Scholars quote it constantly. Nobody seriously questions whether we have an accurate version of what Homer wrote. How many manuscript copies do we have of the Iliad? About 1800. That’s genuinely impressive. But it’s not even remotely close to the New Testament’s numbers.

Julius Caesar’s account of the Gallic Wars, the one where he famously said “I came, I saw, I conquered,” has about 250 manuscripts. And again, scholars trust these works completely. They build entire academic careers on studying these texts. But the Bible has exponentially more manuscript evidence than any of them.

When I first saw these numbers laid out side by side, I realized something crucial. The question isn’t “Can we trust the Bible without the originals?” The question is “If we trust every other ancient text with far less evidence, why would we not trust the Bible with vastly more?”

It’s Not Just About Quantity

But having a lot of manuscripts isn’t the only thing that matters. We also need to talk about timing, about how close these copies are to when the originals were actually written. Scholars call this the time gap, and it’s crucial for determining reliability.

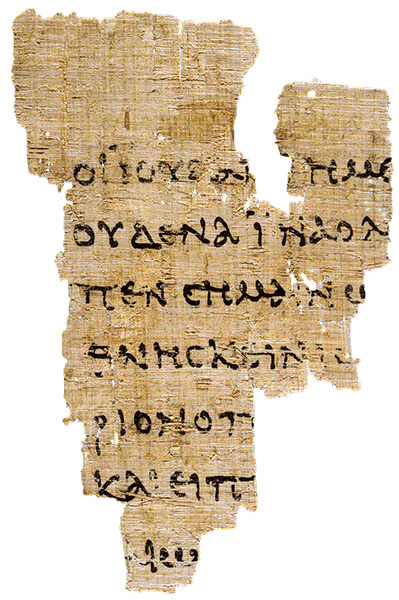

There’s this tiny fragment of papyrus called the John Rylands Papyrus, about the size of a credit card, that contains just a few verses from the Gospel of John. Specifically, it’s the part where Jesus is standing trial before Pilate. Scholars date this little scrap to somewhere around 125 to 200 AD. The Gospel of John was probably written around 90 to 100 AD. That means this copy was made somewhere between 25-110 years after John wrote the original.

Let me put that in perspective with those other ancient texts we trust. Homer’s Iliad was written around 800 BC. Our earliest manuscript copy is from around 400 BC. That’s a four-hundred-year gap between the original and our earliest copy. Julius Caesar wrote about the Gallic Wars around 50 BC, and our earliest manuscript is from about 1000 AD. That’s a nine-hundred-year gap.

The New Testament? In many cases we’re talking about gaps of just thirty to a hundred and fifty years. Some fragments are even closer than that. We have more manuscripts, and we have them from much closer to the original writing time. It’s not even a competition (refer back to chart above).

The Science of Figuring Out What the Original Said

Now here’s where things get really fascinating. There’s an entire academic discipline called textual criticism that exists specifically to handle this exact situation. Don’t let the word criticism scare you. It doesn’t mean criticizing the Bible or tearing it apart. It means carefully comparing all these thousands of manuscripts to figure out what the original text most likely said.

Think of it like this: Imagine your grandmother had this incredible chocolate chip cookie recipe, but she never wrote it down. She taught your mom, who taught you, and you taught your kids. But somewhere along the way, someone said “one cup of sugar” instead of “one and a half cups.” How would you figure out what Grandma actually said? You’d ask everyone. You’d compare notes. If fifteen people remember “one and a half cups” and only two remember “one cup,” you’d be pretty confident about what the original recipe was, right?

That’s essentially what textual critics do, except instead of asking family members about recipes, they’re gathering manuscripts from libraries and monasteries all over the world. They compare them line by line, word by word, sometimes letter by letter. When they find differences between manuscripts, they use specific rules and methods to determine which reading is most likely original. It’s rigorous academic scholarship that’s been refined over centuries.

One of the greatest textual critics of the twentieth century was a scholar named Bruce Metzger who spent his entire career at Princeton studying New Testament manuscripts. Metzger was recognized by believers and skeptics alike as one of the absolute leading authorities in the field. Here’s what Metzger concluded after decades of research. Because of the sheer number of manuscripts we have and because of how close they are to the original time period, we can reconstruct the original New Testament text with tremendous confidence. He put it at around 99% accuracy for the meaningful content.

99%. Let that number sink in for a minute. The remaining 1%? Those are mostly spelling differences, word order changes, or little scribal slips that don’t affect any doctrine or teaching whatsoever. We’re not talking about missing chapters or invented stories or anything that changes what the text actually means.

When Critics Say the Bible Has Been Changed

I know some of you have heard people say the Bible has been changed over the centuries. That it’s been corrupted. That we can’t really trust what we’re reading. I want to address that head on, because yes, there are differences between manuscripts. Scholars call these variants, and they’re completely open about them.

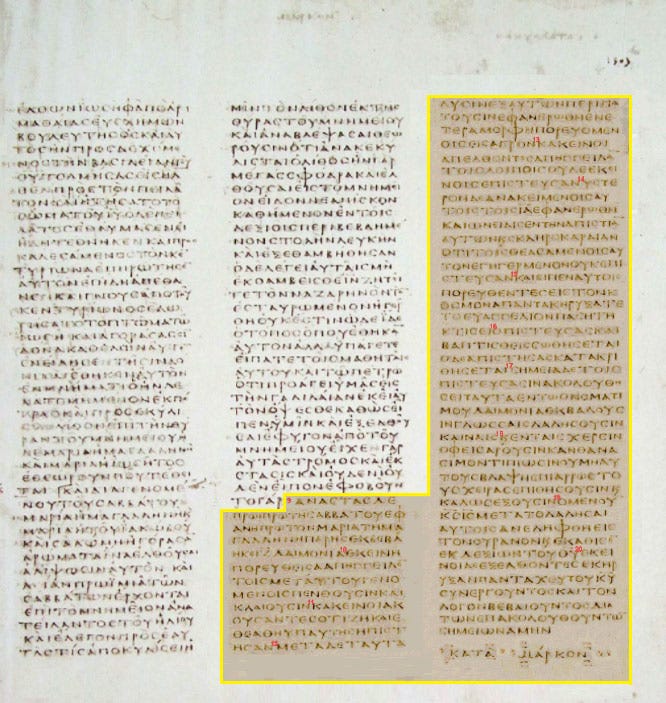

One example that comes up a lot is the ending of Mark’s Gospel. Some early manuscripts include Mark 16:9-20, and some don’t. You know what good modern Bibles do with information like that? They tell you right there in the footnotes. They don’t hide it. They don’t pretend the variant doesn’t exist. They lay it out in plain view and let you know exactly what’s going on.

Here’s the crucial thing though. Even with these variants, no major Christian doctrine depends on a disputed passage. The deity of Christ? That’s taught throughout the New Testament in passages nobody disputes. The resurrection? Confirmed in multiple books. Salvation by grace through faith? All over Paul’s letters in manuscripts that match each other almost perfectly. The variants exist, but they don’t change anything essential about what Christians believe or how we understand who God is.

Why Having Thousands of Copies Actually Protects the Text

A lot of people think of the Bible’s transmission like a game of telephone. You know, where one person whispers a message to the next person, who whispers it to the next person, and by the time it gets to the end of the line it’s completely different. “I like pizza” becomes “Mike’s in a blizzard” or something equally ridiculous. That’s how many people imagine the Bible was passed down. One guy wrote it, told another guy, who told another guy, and two thousand years later it’s totally different from what started.

But that’s not at all what happened. The Bible wasn’t passed down in a single line like telephone. It was copied and distributed widely and quickly from the very beginning. So you don’t have one line of transmission. You have hundreds of independent lines, then thousands, all running parallel to each other across different geographical regions.

If one scribe in Egypt makes a mistake copying John’s Gospel, but scribes in Syria and Rome and Asia Minor all have correct copies, we can easily spot the error. The manuscripts actually correct each other. It’s a self-checking system. By the end of the first century, Christian communities existed all over the Roman Empire. Spain to Syria. North Africa to Asia Minor. They were all reading and copying the same texts. This widespread distribution protected it.

Think about it practically. If someone in Rome tried to change a passage, Christians in Antioch would immediately notice because their copies didn’t match. The broader the distribution, the harder it becomes to corrupt the text because you’d have to somehow coordinate changes across dozens of independent communities that didn’t have phones or internet or any way to secretly collaborate on textual alterations.

What This Means When You Pick Up Your Bible at Home

So when you pick up your Bible at home, whether it’s the NIV or ESV or NRSVue (my personal favorite) or any other major translation, you can have confidence that what you’re reading is what the original authors wrote. Not because of blind faith. Not because someone told you to just trust it. But because of rigorous historical and textual scholarship that’s been tested and verified and peer-reviewed by scholars who spend their entire careers on this exact question.

So, we don’t have the originals. But honestly? We don’t need them. The multitude of manuscripts we do have gives us a window into the past that’s clearer and more reliable than for any other ancient text. Not even close. When I first found out that we don’t have the originals, I thought it was a crisis. Now I understand it’s actually the strongest evidence we could ask for that the text has been faithfully preserved.

I hope you can rest a little easier knowing that the book you hold in your hands is trustworthy because of the manuscript evidence.

I write this newsletter independently. If you value this perspective, a paid subscription ($8/month or $80/year) or a cup of coffee helps keep it sustainable.

What I find interesting isn’t whether the Bible is “reliable” in an institutional sense, but that the text survived in spite of empire, not because of it. What came later was control, canon, and certainty. What came first was argument, plurality, and communities arguing about meaning in real time. That tension matters more than manuscript math.

I’m off on a tangent here, but I would love for you to write about what is meant by “salvation.” What was Jesus saving us from? I do not believe in hell as a place where some go after death. It’s not consistent with the concept of a loving God. Could you please expand on this in one of your essays or other writings?