3 Myths About How the Bible Was Put Together That Need to Go Away

Part 3: What Really Happened When the Church Decided Which Books Made the Cut

I’ve been teaching a three-week class on biblical reliability, and we hit the third week last night. The first two weeks covered manuscript evidence and archaeology. Folks asked good questions. I shared what I learned here on Substack, and you seemed to appreciate it.

But week three was different. Week three is where things get spicy. Because week three is where we talk about how the Bible was actually put together. How did we end up with these 27 books in the New Testament and not others? Who decided? When did they decide? And was it actually decided at all, or did someone just announce one day that this was the Bible now and everyone had to deal with it?

The moment I put up the slide about canon formation, I could see the wheels turning. What about The Da Vinci Code? Was it Constantine? Did a bunch of bishops vote on which books to include?

Here’s the thing about how the Bible was assembled. Almost everything you’ve heard about it is probably wrong, and it’s not because you’re gullible. It’s because popular culture has been feeding us the same myths for decades and they’ve taken root in our collective consciousness. So let me tackle the three biggest misconceptions I keep hearing, because if you’re going to trust the Bible, you deserve to know how it actually came to be.

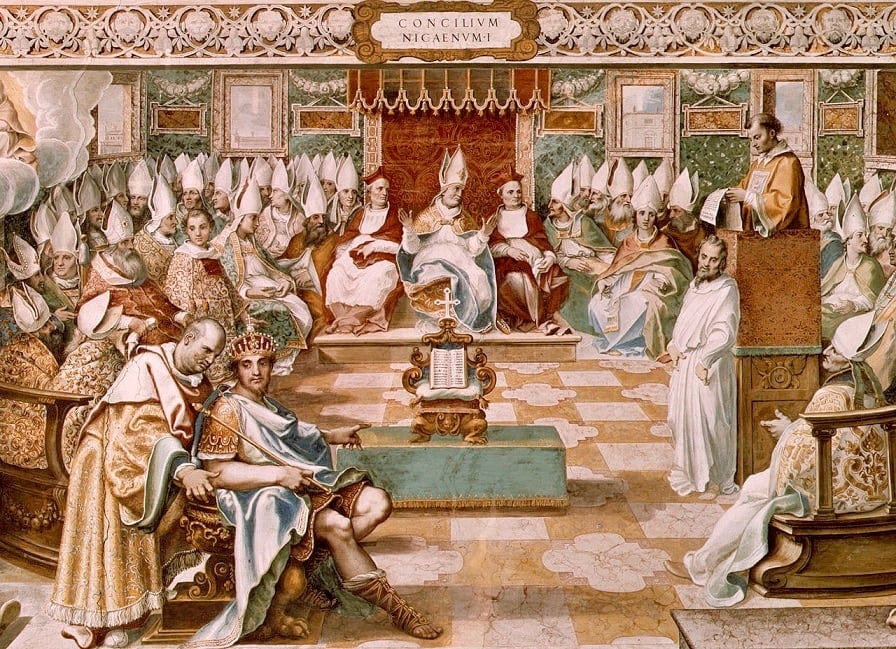

Myth 1: The Council of Nicaea Decided Which Books Made the Bible

This is the big one. Thanks largely to The Da Vinci Code, millions of people believe that in 325 AD, Emperor Constantine called together a council of bishops at Nicaea, and they voted on which books belonged in the Bible. Maybe they took a show of hands. Maybe some books barely made it in while others barely missed the cut. The image is of smoke-filled rooms and political maneuvering and power plays that determined what Christians would read for the next two thousand years.

It’s a compelling narrative. It positions the Bible as a product of political conspiracy rather than divine inspiration. It suggests that different books might have made it in if different bishops had shown up that day. It makes the whole thing feel arbitrary and suspect.

There’s just one problem. None of it happened. Truly.

The Council of Nicaea met to address the Arian controversy about whether Jesus was fully divine or a created being. They hammered out what would become the Nicene Creed. They discussed church governance and the date of Easter. They did not discuss the biblical canon. Not even a little bit. There are detailed records from people who attended the council, including Eusebius and Athanasius. None of them mention anything about deciding which books belonged in Scripture.

By 325 AD, the books we now call the New Testament had already been circulating for over two centuries. Churches across the Roman Empire were already using them. The earliest complete list we have of the 27 New Testament books comes from Athanasius in 367 AD, but he wasn’t inventing anything. He was documenting what churches had already recognized for generations. The canon wasn’t created by vote. It was recognized through consensus over time.

The Nicaea myth persists because it fits a narrative we want to believe about institutional religion and power. But the historical record is clear. Nicaea had nothing to do with the Bible’s formation. The bishops were too busy arguing about theology to worry about which books belonged in their Bibles.

Myth 2: Early Christians Had Hundreds of Gospels to Choose From

This one usually comes up when people want to suggest the biblical canon is arbitrary. The claim goes like this. In the early centuries of Christianity, there were dozens or even hundreds of different gospels circulating. Some portrayed Jesus one way, others portrayed him differently. The church picked the four that supported their theology and suppressed all the rest. If different people had been in charge, we might have ended up with a completely different Bible.

The problem with this myth is that it conflates “texts that existed” with “texts that were serious candidates for inclusion.” Yes, there were other gospels floating around in the second and third centuries. The Gospel of Thomas. The Gospel of Peter. The Gospel of Judas. Various other texts that claimed to record Jesus’ teachings or life. But these weren’t all sitting on an equal playing field with Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

The four canonical gospels were written in the first century, within living memory of eyewitnesses to Jesus’ life. They circulated widely from the beginning. By the mid-second century, they were already being treated as authoritative across diverse Christian communities from Rome to Syria to North Africa. When early church fathers like Irenaeus wrote around 180 AD, they referred to “the fourfold gospel” as if this was already established and uncontroversial.

The other texts? Most were written much later, in the second century or beyond. They came from specific groups with specific theological agendas, often Gnostic communities that held radically different beliefs about the nature of God, creation, and salvation. These texts were rejected because they taught a fundamentally different religion and they lacked apostolic origin.

The idea that early Christians were sorting through hundreds of equally valid gospels is simply ahistorical. The four gospels we have were recognized early and broadly. The others were regional texts that never gained widespread acceptance because they failed basic tests of apostolic authorship and theological consistency with what the apostles had taught.

Myth 3: The Canon Was Closed by Church Authority

This myth takes a different form than the first two. Instead of claiming the canon was decided by vote or chosen from hundreds of options, it suggests the canon was imposed from above by church leadership. A pope declared it. A council mandated it. Someone with authority said “these books and no others,” and that became binding on all Christians.

The reality is messier and more interesting. The canon formed gradually through what scholars call “corporate reception.” Churches across the known world, operating largely independently because there was no centralized authority in the early centuries, came to recognize the same set of books as authoritative. This was because these books bore the marks of apostolic origin, theological soundness, and spiritual power.

Different churches had different books they were uncertain about. Some questioned Revelation. Others debated Hebrews or James. But by the fourth century, there was remarkable consensus across incredibly diverse communities. Churches in North Africa agreed with churches in Asia Minor agreed with churches in Rome. Not because of top-down control, but because they recognized the same Spirit at work in the same texts.

When church councils eventually did issue official lists of canonical books, they weren’t creating the canon. They were ratifying what had already been recognized. They were documenting the consensus that had emerged over centuries of use, testing, and discernment. The Protestant Reformation later adjusted this consensus slightly by removing the deuterocanonical books, returning to the Hebrew canon Jesus would have known. But even that wasn’t an arbitrary decision. It was grounded in questions about which texts had always been considered fully authoritative versus which had been helpful but secondary.

The canon emerged through faithful communities recognizing which texts carried divine authority. That’s a much less tidy process than “the pope said so,” but it’s also much more compelling as evidence that these books genuinely are different from others.

What This Actually Means

I’m not trying to convince you that the canon formation process was perfect or that no human politics were involved at any point. Church history is messy because humans are messy, but the broad strokes matter. The Bible we have wasn’t cobbled together by a small group of powerful men making arbitrary decisions to protect their interests. It emerged over centuries through diverse Christian communities recognizing which texts bore witness to the Jesus the apostles proclaimed.

The myths persist because they’re simpler than the truth. A single council making a decision is easier to grasp than centuries of corporate discernment. A conspiracy theory is more dramatic than gradual consensus. But simpler and more dramatic doesn’t mean more accurate.

The canon formation process was long, complex, and remarkably consistent across geography and time. Churches that couldn’t easily communicate with each other came to the same conclusions about which books belonged in Scripture. That kind of widespread agreement, emerging organically rather than by decree, is actually far more compelling evidence for the reliability of these texts than a single authoritative decision would have been.

So the next time someone brings up Constantine or Nicaea or claims the church suppressed alternate gospels, you’ll know better. The Bible wasn’t assembled by conspiracy. It was recognized through discernment. And that recognition happened because Christians across the world encountered the same living God in the same sacred texts.

And honestly, I think that’s a better story than any conspiracy theory could ever tell.

I write this newsletter independently. If you value this perspective, a paid subscription ($8/month) or a $5 cup of coffee helps keep it sustainable.

Very interesting, well-constructed post. I’m familiar with some of what you said but you took it to a new level. You mention that the rejected texts “lacked apostolic origin” or “basic tests of apostolic authorship and theological consistency.” Can you share a little more of what this means to you?